In Southeast Essex County, where the borders of Newark, Bloomfield, and the Oranges blur, nature is staging a revolt. Beneath the cracked pavement and flooded basements of these communities lies an ancient geological truth: This land was once a network of springs, a waterlogged boundary that modern maps erased but never truly subdued. Now, as climate change fuels heavier rains and insurers retreat from repetitive disasters, Essex faces a reckoning. The question is whether its leaders will heed science—or cling to the political fiction that small towns can wall off a shared crisis.

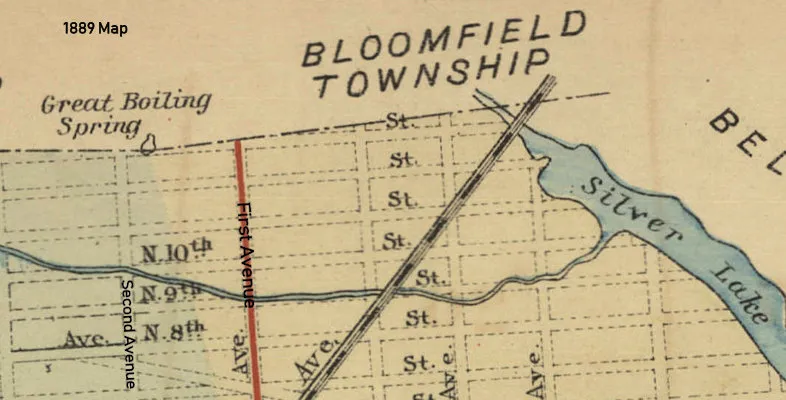

For decades, municipal boundaries here have served dual purposes. They carve up school districts, tax bases, and resources in ways that perpetuate inequity. But they also fracture responsibility for the valley’s flooding, a problem that laughs at lines on a map. Four cities—Newark, Bloomfield, East Orange, and South Orange—are already drowning in the same waters, yet solutions remain siloed. Local officials deploy Band-Aid fixes: clearing drains, patching roads. One frustrated advocate likens it to “battling a lake with a hand mop.” Meanwhile, the minor valley’s natural springs, long buried under concrete, are reasserting themselves, pooling in streets and living rooms.

Women bear much of the burden in the aftermath of climate events. And this will be the case in South Bloomfield. It is not only during powerful storms, like Hurricane Sandy, where 60% of individuals poisoned by CO in the aftermath of the storm were women, but also in the lack of resources to maintain a home with repeatedly flooding. New Jersey ranks near the bottom (43) in pay equity for women with children.

The path forward is no mystery. It requires a regional authority to oversee buyouts of flood-prone homes, replacing them with catchment basins and green infrastructure. It demands modernized sewers and honest conversations about zoning—about stopping construction in harm’s way. But progress stalls in the shadow of parochialism. Too many planning decisions, critics argue, are shaped by political alliances rather than hydrological models. “We’re entrusting survival to people’s friends, not experts,” one biologist told me, citing stalled county-state collaboration.

The cost of denial grows by the season. Federal flood insurance, a lifeline for homeowners, may soon collapse here; why underwrite houses in a former wetland nature is reclaiming? Yet buyouts, a proven tool in climate mitigation, remain taboo. No mayor wants to shutter blocks or cede control, even as residents bail out their basements.

Essex County is not unique in clinging to outdated maps. From Houston to Miami, communities gamble against geology. But New Jersey’s density leaves little room for error. Every dollar wasted on piecemeal fixes—every delay in merging technical expertise with political will—deepens the eventual bill.

The lesson is clear: Water follows gravity, not gerrymandered borders. Until Essex County’s leaders unite to meet this threat, the valley’s springs will keep rising, washing away the illusion that small towns can segregate their way to safety.