At its core, feminist urbanism demands that city planners ask, “Does your class, whether it is gender, race, or socioeconomic, dictate your options in this city?” This question is especially pertinent in New Jersey, where systemic and institutional inequality has long dictated who has access to housing, reliable transportation, and public space.

Transportation, for example, disproportionately burdens women in all cities, including Newark. Women are more likely to use public transit, yet most transportation planners are men, and over 80 percent of civil engineers are men. This matters; feminism isn’t a required course for planning or engineering, so the bare minimum option is one with the experience of not being a cisgender white man. One can’t plan for someone not in the room, especially someone without critical training. A 2018 study demonstrated that women are more likely to engage in trip-chaining with public transit than men, meaning performing multiple tasks and making stops en route to a single destination. The Metro transit infrastructure is designed around 9-5 work commutes and fails to account for these sorts of patterns. It leaves out working-class women and puts caregivers at a disadvantage. In addition, NJ Transit, the public transit serving Newark, seems way more concerned with “suburban” commuters (who are more white) than those who live in Newark (whose biggest demographic, 47%, is Black), regardless of gender.

Feminist urbanism demands a complex systems approach. This framework reveals the intricate connections between schools, jobs, recreation, housing, commerce, and transportation and class's power dynamics within those connections. It ensures that urban development addresses the interconnected aspects of city life.

NJ Transit could expand Newark bus routes, extend the light rail to South Newark and East Orange, implement attractive bicycle track infrastructure, and ensure that public spaces around transit hubs are supported with thriving cooperative businesses, schools, childcare centers, and state & county-funded public cultural events. A 2020 World Bank study found that when transit systems incorporate women’s mobility needs, ridership increases significantly, and cities experience enhanced economic productivity.

In Newark, New Jersey, where the astir sidewalks echo with diversity and ambition, there is an opportunity to adopt feminist urbanism, which would benefit all genders. Feminist urbanism is a lens that can support Newark in addressing its historic and persistent transportation inequities and housing challenges with a metric that considers more than market indicators.

This is not merely a theoretical exercise. Studies demonstrate that urban planning historically privileges male perspectives, leading to infrastructure that is sexist and inadequately serving women, children, seniors, and lower-income residents. Newark can be a model city by reversing this trend by redesigning its city so that public spaces, transit systems, and housing policies reflect the realities of everyone, not just those who are viewed as more valuable simply because they have more money.

BUT this can’t solely be about transit.

We also have to think about housing, a problem that is impacting people in Metro areas all across this country, as well as in Western Europe, and Canada.

We got here by siloing housing, transportation, labor, race, and gender.

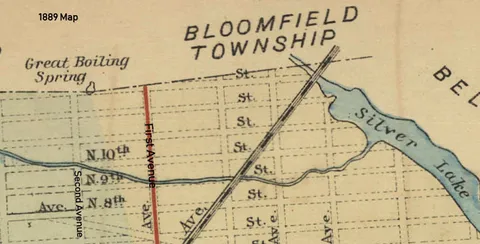

Newark’s affordable housing crisis (which is a Metro affordable housing crisis as this is also in Montclair, Bloomfield, and Jersey City…) also requires feminist-informed solutions. Newark’s median household income is just over $46,000 (the state median is $112,000). The ‘imperfect horrific’ storm of racism, sexism, a lack of enforcement of the Fair Housing Act, racial discrimination by area employers, and gentrification creeping in from all sides put long-time residents at risk for displacement. Unpartnered parents, predominantly women, representing 63% of Newark households, are particularly vulnerable. Women, on average, earn less money than white men,and Black women earn less than the average woman.

Donate Femininomenon! Urbanism Campaign

Integrating feminist principles into housing policy means designing homes that consider the realities of caregiving, multi-generational living, fluctuating incomes, AND the options of women not being married to men. Vienna’s Frauen-Werk-Stadt (Women’s Work City) showcases the power of feminist urbanism in action. Its social housing project, designed with a feminist lens, includes ample communal spaces, proximity to childcare facilities, apartments with layouts that support caregiving, and costs that unpartnered cis and trans women can afford. It is also inclusive of elderly, immigrants, and people with disabilities.

Newark could adopt similar strategies, prioritizing housing developments integrating childcare, elder care, co-working spaces, accessible for those with disabilities, and robust public transit links. Additionally, a feminist housing approach could take a less strict approach to means testing, a revisiting of the highly flawed HUD AMI calculation, adopting a more universal approach so as not to recreate segregation by class and reducing displacement, resulting in the development of a stable cooperative community.

Newark’s public spaces in its Central Ward neighborhood are already inclusive and welcoming, and this paradigm can be expanded to all of Newark.

A feminist lens for Newark would also involve viewing Newark as a part of the Metro and working with other cities, including New York, on solutions to the climate crisis. People not being able to live near transit (within half a mile) means they may have to get a car and engage in driving to qualify for housing, which pushes sprawl and harms us all. Housing that everyone can afford is no longer a “nice to have.” It is mandatory if we are taking the climate crisis seriously.

While feminist urbanism directly benefits women and historically excluded & marginalized groups, its principles create ripple effects that enhance city life for all. A city that works for women works for everyone. Affordable, accessible housing creates pro-social communities with less class segregation. Efficient, inclusive public transit, good walking paths, and bicycle infrastructure reduces traffic congestion, cuts emissions, and boosts economic growth.

By embracing feminist urbanism, Newawk could reimagine its urban space and be a model to all of Urban America of what a just, sustainable, and Feminist urbanism could look like.